A bit of Valentine history

Valentine’s Day is possibly the most worldwide of celebrations: heart-shaped candies and flowers are exchanged on February 14th in the U.S., China, Brazil, Iran, and almost everywhere else on the planet. But originally, the observance had nothing to do with romantic love, and virtually nothing is known about the man—or men—after whom the day is named.

Multiple Saint Valentines?

There were several—perhaps dozens—of “Valentines” in early Christian history; it was a fairly common name in Imperial Rome. Many Valentines were Christians persecuted and martyred by Roman authorities, and the Church conflated their deeds, both real and imagined, in creating a composite “Saint Valentine.”

The two most likely actual candidates are Valentine of Interamna, who was consecrated a bishop in AD 197 and persecuted by Emperor Aurelian (this was before the Empire became officially Christian) and Valentine of Rome, who was murdered in AD 496.

Both saints were buried on the Via Flaminia, though in different places. Therefore, the proper way to state the Christian observance day was actually “Saint Valentines’ Day.” Many church frescoes and stained glasses depicted both saints. Almost nothing is known of their lives or deeds, however.

Sacrifice not love

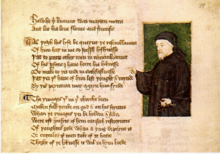

Since both of the most prominent Valentines (and many of the others as well) had been martyred, the Feast of Saint Valentine was originally associated with sacrifice, not with romantic love. It first became associated with romance due to Chaucer, who mentioned it in Parliament of Fowles in 1382: “For this was on St. Valentine’s Day, when every bird cometh there to choose his mate.”

Other poets and storytellers gradually followed Chaucer’s lead and spoke of the day as the beginning of spring and the time when the birds came out and romantic love would flourish.

But it’s still winter

However, if you’re shoveling snow from your driveway after a blizzard on February 14th, you might be wondering just what the heck Chaucer was thinking.

The answer is that the Julian calendar was off—way off—by Chaucer’s time.

The Romans recognized that the year is not 365, but rather, 365 ¼ days long, and so invented the leap year—the signature feature of the Julian calendar. However…the year is actually twenty minutes shorter than 365.25 days—the Julian calendar made the year too long.

The result was that the start of spring (and all other fixed events) sneaked “backward” about three days every four centuries, so that thirteen centuries after the Julian calendar was introduced, in Chaucer’s time, spring was indeed coming—and the birds were mating—in mid-February.

Re-branding a saint

This brings us back to the Christian Saint Valentines. The Christian Church and religion spread rapidly worldwide in large part due to history’s first successful mass marketing campaigns, many of which involved what we call today “re-branding.” Recognizing that resistance to their new religion would be less if pagan cultural practices were incorporated into Christianity rather than having it replace them, Church authorities installed new, modern versions of Pagan holidays such as the winter solstice celebration (Christmas), “day of the dead” festivals (All Saint’s Day), and so forth.

Valentine’s Day evolved in part because another extremely common celebration in almost every society, then and now, is the “coming of spring.” The Romans had Lupercal, a several-days-long festival of drinking, dancing, and “making whoopee,” which was a perfect time to install a more Christian celebration.

From sacrificial mourning to celebrations of love

The thing is, when early Christian authorities decreed February 14th to be the day to revere Saint Valentine(s), the date was in winter—ideal for mourning and remembrance. It was only due to the creeping inaccuracy of the Julian calendar that by Chaucer’s time, the date was when the snow started melting and the birdies started singing. People began to regard the day as a marker of the coming of spring. (In 1582 Pope Gregory fixed the problem, but the British didn’t adopt the Gregorian Calendar until 1752.)

The Church, still skilled in re-branding, decided to respond to this (unstoppable) trend by making up some legends to associate one Valentine or the other with romantic love. The earlier Valentine, of Interamna, was now said to have performed secret marriages for Roman soldiers who had converted to Christianity (still highly illegal at the time). He was also purported to have cut out paper hearts as a token of affection for his friends, and he supposedly wore an amethyst ring (the February birthstone). He also cured a young girl, the daughter of his jailer, of blindness. All these legends, and more, were piled on well after the fact, however, by chroniclers ranging from the 8th-century Bede to 18th-century ecumenical councils.

Paper hearts

Valentine, or Valentines, proved to be a highly reusable and malleable symbol. When the Christian Church realized that they didn’t have a coming of spring celebration, they changed St. Valentine from a bishop who had had his head chopped off to a hopeless romantic who married people in secret and handed out paper hearts (a much happier celebration). Love was (officially) in the air!

Add to all that the remarkable greeting card industry that sprang up during the Victorian era and you have our modern version of Valentine’s Day.

By guest contributor: Kevin M. Lewis

Images from Wikipedia